A New Way to Treat Craniosynostosis?

Posted

19 Oct 23

A new Cell Stem Cell publication by Ostrow researcher Jianfu Chen shows how the lymphatic system and skull stem cells may help kids with a rare birth defect.

CRANIOSYNOSTOSIS IS A BIRTH DEFECT in which the bones in a baby’s skull fuse too early — before the brain is fully formed. It happens in 1 in nearly 2,200 births and has been studied for a long time. But, even though there was a wide swath of research about the defect, most studies focused on the skull deformities and not on the learning and social problems kids with craniosynostosis suffered.

That’s what inspired Associate Professor Jianfu Chen to study the neuroscientific aspects of the disorder. In a new study published in the journal Cell Stem Cell, Chen used a mouse model to study craniosynostosis in a whole new way.

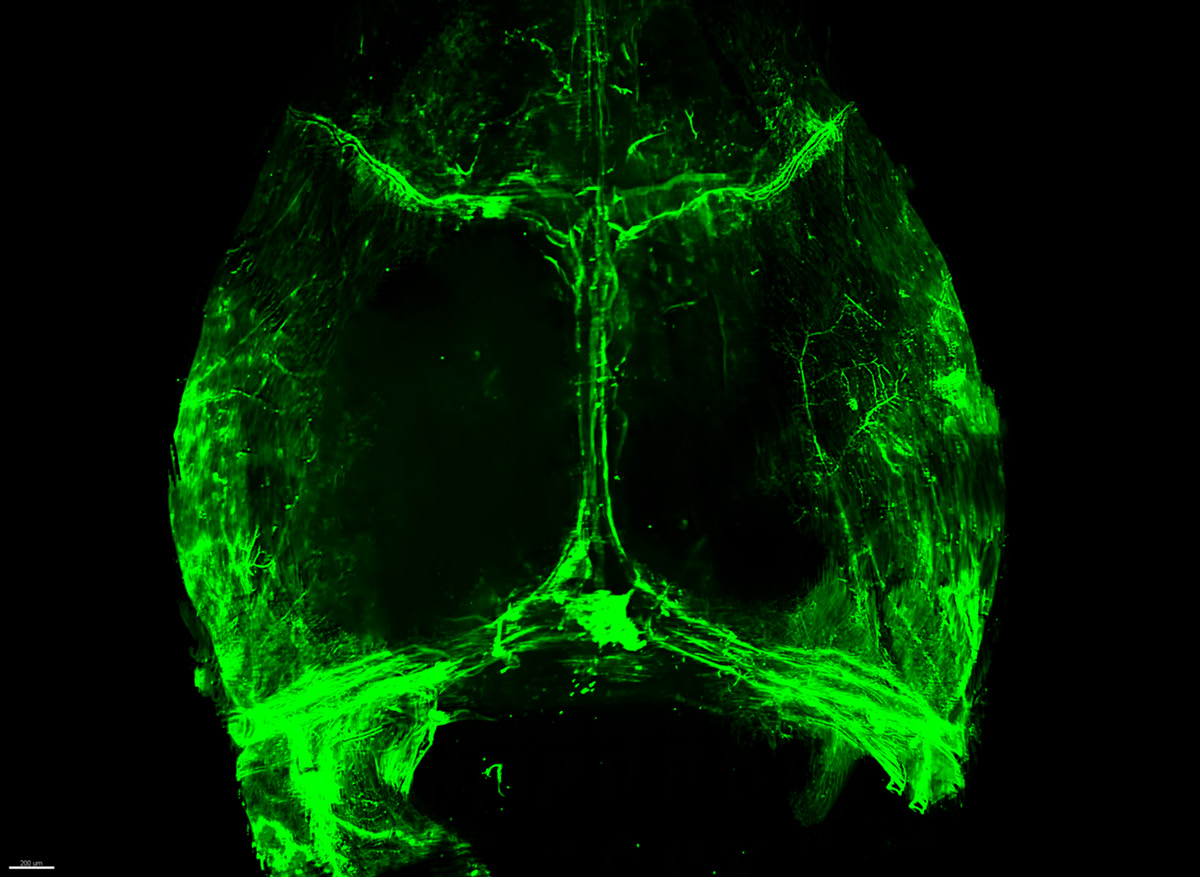

In the study, he focused on the lymphatic system — a network of organs, vessels and tissues that move a colorless fluid called lymph back to your bloodstream. Researchers only recently re-discovered that the brain has a lymphatic system at its border, called meningeal lymphatics, located between the skull and the brain.

“Our craniosynostosis patients have skull and brain problems, so we thought maybe something in between has a problem that leads to both types of defects,” Chen explained. By implanting back skull stem cells, the researchers saw a restored lymphatic system and improved cognitive function in the animals.

Focus on the Lymphatic System

Chen says this is the first time the lymphatic system has been functionally linked to craniofacial disorders, and the new knowledge could lead to better future management of craniosynostosis. The current treatment is a complex surgery to cut the skull into different pieces. The surgery can cause a lot of blood loss and sometimes has to be repeated when the bones re-fuse as the child develops. Chen says interventions in the future could treat the malfunctioning lymphatic system using pharmacological or stem cell approaches as new therapeutic strategies for craniosynostosis.

“We know the skull and brain are anatomically adjacent,” Chen said, “but we didn’t know how they talk to each other. But now we know the skull communicates with the brain through the lymphatic system.”

When Chen arrived at USC six years ago, he and University Professor and Associate Dean of Research Yang Chai PhD ’91, DDS ’96 (corresponding author) started to talk and realized there was a whole area of neuroscience that was poorly explored: the neuroscientific aspect of craniofacial problems. It set them off on an interdisciplinary research path by integrating Chen’s neuroscience with Chai’s craniofacial expertise. “We didn’t know what we would find,” Chen explained, “but we felt there was something there.” He added that Li Ma, Qing Chang and other trainees worked hard to help find one piece of the puzzle — the lymphatic system — that integrates the skull with the brain.

In the future, he will continue the work by studying how the lymphatic system works within the skull —where it is, how it is structured and what its functions are in homeostasis, injury repair and regeneration. It’s a departure from the way science has been done in the past, he says: “The skull people study the skull, and the neuroscientists study the brain, but it’s a super exciting time to study how they communicate.”