Could stem cell- or molecular-based treatment be the solution to temporomandibular joint disorders?

Posted

29 Jun 21

A new study, led by Amy Merrill-Brugger, could lead to new treatments for the common disorder.

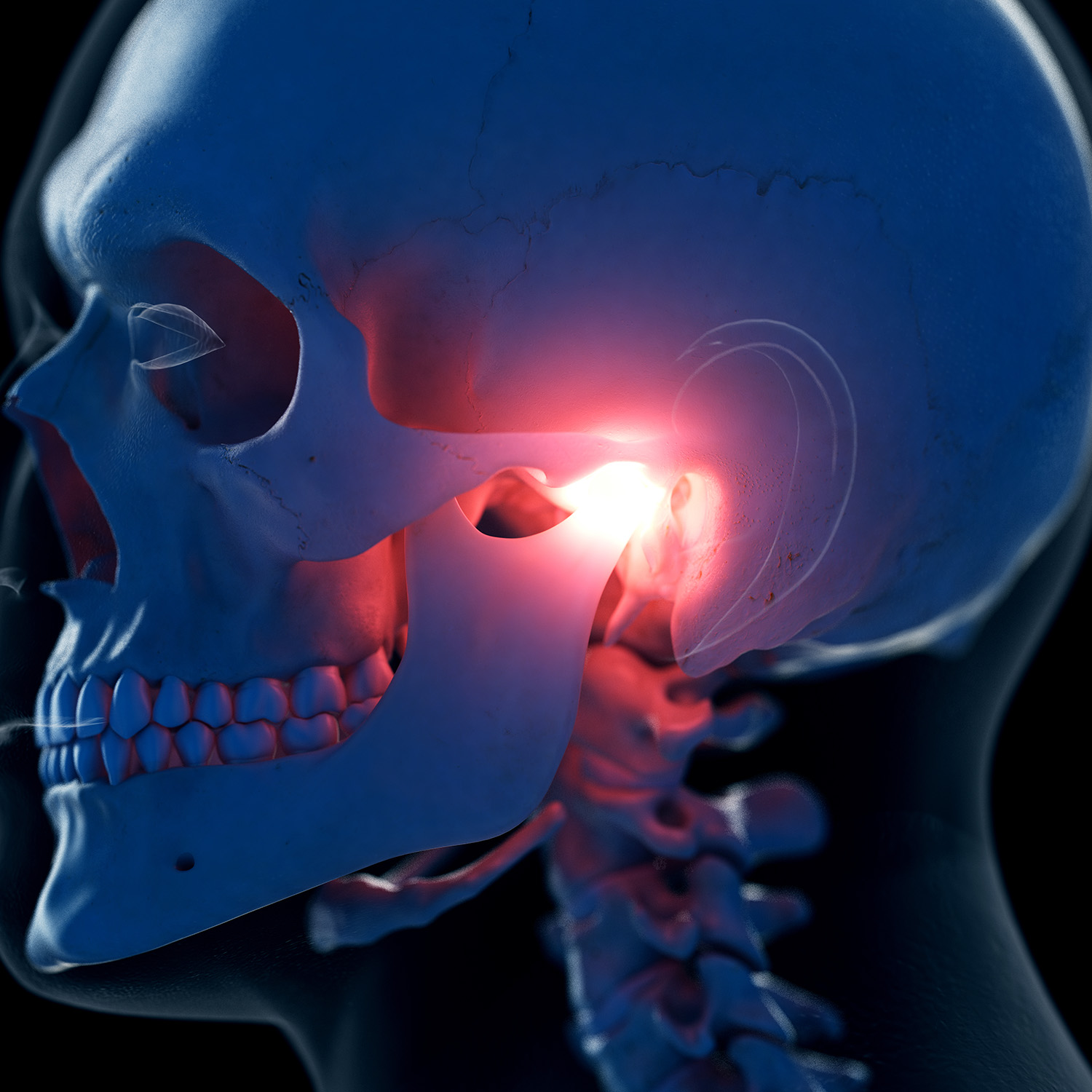

OUR JAWS ALLOW US TO TALK, chew, swallow, sing and even yawn. All these activities require the temporomandibular joints, which connect the lower jaw to the base of the skull and drive its movement up and down and side to side.

When disorders in temporomandibular joints arise — a commonly occurring condition that the National Institutes of Health estimate affects between 5 and 12 percent of the American population — it can cause pain, discomfort and disability.

There is not a lot known about what causes temporomandibular joint disorders (TMD), but a new study led by Associate Professor Amy Merrill-Brugger PhD ’05 could change that, even giving healthcare providers new stem cell- and molecular-based interventions to promote tissue repair and regeneration in patients suffering from TMD.

In the five-year study, funded by a $2.3-million grant from the National Institutes of Dental and Craniofacial Research, Merrill-Brugger and her team will study embryonic development of the tissue connecting tendons to bone.

“Tendon and bone are connected by a specialized connective tissue called the enthesis,” Merrill-Brugger explained. “The enthesis plays a very important role in joint mobility because it allows muscles to move bones. We hope to discover how entheses that promote jaw movement form during embryonic development.”

Damage to this connective tissue (enthesis) can result from either physical injury or disease and is linked to TMD, she added.

“By identifying the cells and genes that build jaw entheses in development, this study has the potential to guide novel strategies to promote tissue repair and regeneration in temporomandibular disorders.”

Merrill-Brugger earned a bachelor’s degree in molecular, cellular and developmental biology from the University of California, Santa Barbara and a PhD in biochemistry and molecular biology from USC, before embarking on an independent academic career in biomedical research.

“I love how science demands imagination and innovation, while also offering the thrill of discovery and an endless potential to improve the health and well-being of others,” she said.

Merrill-Brugger joined Ostrow in 2010 as an assistant professor with a dual appointment with the Keck School of Medicine of USC. She was promoted to associate professor with tenure in 2018.

This year, the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC was ranked No. 4 in research funding by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, thanks in part to grants like this earned by Merrill-Brugger.

“Competition for funding is intense,” she said. “Having our work and ideas recognized by the NIDCR with this grant is truly energizing.”

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DE029850. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.